Mono-Gram - Valley Fever Cases in US Southwest Rising Fast

April 2, 2013

CDC: Valley fever cases in US Southwest rising fast

From Mar 28, 2013 (CIDRAP News)

Coccidioidomycosis, or valley fever, a fungal infection that causes influenza-like symptoms and often leads to hospitalization, has increased "dramatically" in the US Southwest in recent years, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported today.

The five affected states that report cases—Arizona, California, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah—recorded just 2,265 in 1998, or 5.3 per 100,000 population. By 2011 the number reached 22,401 cases, or 42.6 per 100,000.

Reasons for the increase are unclear, but possible factors include environmental and population changes, evolving surveillance methods, and greater awareness of the illness. Despite the rising number of cases, it appears that mortality rates have stayed about the same.

"Valley fever is causing real health problems for many people living in the southwestern United States," said CDC Director Tom Frieden, MD, MPH, in a press release. "Because fungus particles spread through the air, it's nearly impossible to completely avoid exposure to this fungus in these hardest-hit states. It's important that people be aware of valley fever if they live in or have traveled to the southwest United States."

Valley fever is caused by inhaling the soil-dwelling fungus Coccidioides, which is found in dry areas of Mexico and Central and South America as well as the southwestern United States.

Not everyone who is exposed gets sick. For those who do, the infection typically causes a self-limiting flu-like illness that can last weeks or months. Some people suffer severe or chronic lung disease. The infection spreads to other parts of the body in less than 1% of cases.

Seventy-five percent of patients are sick enough to miss work or school for about 2 weeks, and more than 40% need hospitalization. Hospitalization costs average about $50,000.

From 1998 through 2011, 28 states and Washington, DC, reported a total of 111,717 coccidioidomycosis cases. Arizona alone had 66% of those, while California had 31%. In the five southwestern states in which the fungus is endemic, cases increased steadily over the 14 years, except for decreases in 2007 and 2008.

The jumps in the last 3 years of the period were particularly sharp: from 7,464 in 2008 to 12,868, 16,664, and 22,401 in 2009, 2010, and 2011.

The annual rates of increase averaged to about 16% for Arizona and 13% for California, with adjustments for changes in population size and the age and sex distribution of cases. Both rates were significant. The incidence was highest in people age 60 and older, except in California, where those 40 to 59 were hardest hit.

While cases have clearly increased, a study published last year found that coccidioidomycosis mortality rates stayed fairly stable at about 0.6 per 1 million person-years between 1990 and 2008.

The upward trend in valley fever cases could be related to changes in weather, which could impact where the fungus grows and how much of it is circulating; higher numbers of new residents; or changes in the way the disease is detected and reported to the states or CDC. Soil disturbances caused by construction and other human activities are another possible contributing factor.

Greater awareness of the disease might have triggered increased diagnostic testing and reporting. The disease is estimated to be the cause of 15% to 29% of community-acquired pneumonia cases in areas where Coccidioides is highly endemic, but a 2006 study suggested that the illness is "greatly underreported."

Doctors and patients should know that the symptoms of valley fever are very similar to flu or pneumonia symptoms and a lab test is the only way to tell if an illness is valley fever or not. Not everyone who gets Valley Fever needs treatment, but for people at risk for the more severe forms of the disease, early diagnosis and treatment is important. The best way to treat Valley Fever still needs to be studied, especially with the number of cases continuing to rise.

The role of antifungal treatment for valley fever is controversial, but it is recommended for certain groups. Although no proven preventive measures are available, the CDC suggests that people in affected areas should consider trying to reduce their exposure to dusty air, which may contain the fungal spores.

There is a need for more awareness of this infection among healthcare providers and persons living in endemic areas. Healthcare providers should be alert for coccidioidomycosis among patients of all ages who live in or have traveled to endemic areas. Persons in endemic areas should consider trying to reduce exposure to dusty air, which might contain spores.

To access the article, please visit the following CDC website:

http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6212a1.htm?s_cid=mm6212a1_e

For further information on coccioidomycosis, please visit the following CDC and California Department of Public Health (CDPH) websites:

http://www.cdc.gov/fungal/coccidioidomycosis/

http://www.cdph.ca.gov/HealthInfo/discond/Pages/Coccidioidomycosis.aspx

For a good overall resource on valley fever, go to: https://www.vfce.arizona.edu/ValleyFeverInPeople/Diagnosis.aspx

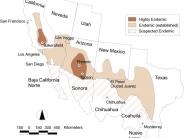

In looking at the maps on the following page, it is unclear how far north into Inyo and Mono County the definition of an “endemic area” applies. However, whether we live there or not, we all visit and have stayed in endemic areas, have traveled through them, and have been exposed to dusty conditions caused by wind or construction. Our exposure to dust which is potentially contaminated with spores is bound to increase after 2 dry winters and little precipitation on the valley floors.